101 TESTIMONIES

Hi guys,

Please find below our reduced version of a video we’ve prepared about our topic, How can we innovate on the Architect’s education?

Enjoy!

Best

Hi guys,

Please find below our reduced version of a video we’ve prepared about our topic, How can we innovate on the Architect’s education?

Enjoy!

Best

Summary:

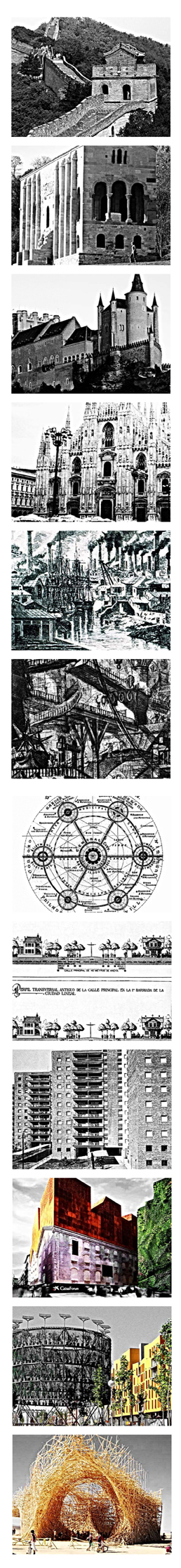

Arch-adapting: An evolution to the past, is an essay on architectural phenomena of adaptation to new realities of architectural creation, from the moment of the conception of an idea until the final architectural outcome. Here, the word outcome substitutes the word construction, on a need to amplify our limit and overpass the hardware sense of constructive spaces/ objects.

¨The evolution to the past¨ concept works with two main poles: The caveman on one side representing the ultimate connection of the human with nature and his tools, a man that finds rather than gets, and ¨The digital caveman¨, as we call him, on the other hand, is representing the high technological man that is able to use technology for re-approaching reality, through high analytical research. Innovation is to be sought after in the beginning of things, in the roots. Innovation is seeded with knowledge and awareness of one’s past.

Nearing the term Arch-adapting, it is important to highlight that these two poles are based on the figure of the simple man, rather than the figure of the architect. What it is tried to be alleged, is that we have been stretched to a moment were architecture is giving out its ¨power¨ again to the user, making him the ¨architect¨ of his environment. And this is the moment were both ¨cavemen¨ share a common ground, they both have direct access to their tools. In a certain moment of the history, Architecture monopolized its tools; tools were exposed only to this certain elite. Now the man alters again to a caveman, a ¨digital caveman¨ that requires to implicate and adapt himself to the advanced means available. The architect here does not create a predetermined spacial situation, rather a platform that offers the tools and the knowledge required for one to come to be autonomous, self-sufficient and part of greater network of exchange. A platform were nature is deeply involved, were materiality originates an architecture adaptive to the environment, were real time data give flexibility and reduction of unnecessary wastes.

The above mentioned essay will be exploring the innovation in Architecture through a quick view on the evolution of architecture in history, by watching closer aspects like locality, tools, collaboration (between people, as well as between people and nature).

Project Authors / Video Design : Nota Tsekoura,Gabriel Bello Diaz

Music & Sound Design : Marios Aristopoulos

Hi everybody.

Let me present our team first, we are Letizia Caprile, Jonas Stahl, Jaime Pages, and myself Maria Prieto-Moreno, students at the IE School of Architecture in Madrid.

Our project for the Venice Biennale is to investigate about how can universities innovate on the Architect’s education nowadays.

Our purpose for these two years is to collect information about this topic interviewing influential figures in the global architectural scene, architects and people related with the sector in order to write a book with the “101 Testimonies on Innovation in the Education of Architects”

During our stay in Venice, we lived a great experience and we had the chance to interview a really good list of architectural leaders on the sector. Around 20 interesting testimonies will become documentaries for the book. We had diverse responses,very instructive all of them. Find below a list with some of the people filmed:

– Toyo Ito

– Jean Nouvel

– Patrik Schumacher (Zaha Hadid)

– Emilio Tuñon

– Alberto Campo Baeza

– Eric Gili from Cloud 9

– Winy Mass (MVRDV)

– Peter Murray

– Juan Herreros

– Wang Shu (Premio Pritzer)

– Architectural Association Exhibition Director

– Javier Martin (Technical Advisor for Architecture and Edification)

– Zahra Ali Baba (Curator Kuwait Pavilion)

The intention is to continue during the next two years with these interviews and make an analysis of the responses obtained and try to come with some interesting conclusions.

From now on, we will be posting the videos and interviewee’s profiles on the Spanishlab Academic Platform, we would like to provoke the debate about how to improve the innovation of the architect’s education.

So…. What do you think about how to innovate on the architect’s education?

Thanks

The Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect is a well-documented phenomenon, in which the air-temperature in an urban area is elevated relative to the regional air-temperature due to the trapping of radiation by cities at night and anthropogenic heating during the day. Architects and engineers who design buildings in urban areas typically lack the tools to include the UHI effect in their analysis. For buildings that are climatically sensitive or aim to be net-zero energy, lacking adequate microclimatic design analysis tools constitutes uncertainty. Innovation in architecture is to provide guidance to design teams on both the potential magnitude of annual energy use prediction errors introduced by ignoring urban microclimatic effects, and potential reduction of such errors via the use of microclimatic models.

Coming from the last Architectural Biennale in Venice I have to say that we are currently more and more familiarized to listen about the need to innovate in architecture. There, we could see that there are big efforts from different well-known architects and architectural studies in the use of new materials, new products or new processes. Also, we could check there, in Venice expo and conferences, how to innovate both in products and processes is more than a trend, a real need for the future in architecture.

We also can see literature enough about how to innovate in engineering and construction of the future houses, but not only, as the smart cities are the new way of understand the urbanism.

But talking about innovation in architecture requires analyzing first what we understand by innovation. Continue reading »

The 2012 Biennale was yet another indication that the fantasies of an Architecture by the “People” for the “People” enabled by a resilient infrastructure of -often self-proclaimed- scientific methods, communication, design and fabrication technologies are returning in the collective architectural imaginary, carrying promises of innovation, creativity, sustainability and forming a counter-rhetoric to a malformed professionalism. Faced with this new wave of optimism, which attracts the creative efforts of an ever-growing number of groups and individuals active in and beyond the design world, an inquiry into the emerging tautology between “democratization” and “innovation” seems necessary in order to untangle the implications of this equation, recognize it as a historical and cultural artifact and explore the conditions of its validity.

In his essay In an Open-Source Society, Innovating by the Seat of Our Pants [3], which appeared in the New York times in December 2011, Joichi Ito, current director of the MIT Media Lab, was lauding the Internet as a space of decentralized innovation and creative individualism. Raising the Internet from the level of a technology to that of a belief system, Ito was advocating for a new mode of production, a new ideology and a new ethic pervading the conception, production, distribution and use of immaterial and (more recently) material artifacts: Open Source. Continue reading »

Who’s working in the service of whose vision? Unexpectedly (for me), this was the question that seemed to predominate the “Common Ground” theme of the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale. From the main exhibitions the national pavilions, the contributing exhibitors espoused varying understandings of who or what constitutes the commons implied by the title. Curator David Chipperfield’s explanation of the main exhibition theme in the August 27 printed edition of Architect’s Newspaper acknowledged the theme’s generality as intentional:

I don’t think an exhibition about architecture is agile enough to make precise statements. Clearly the whole theme of Common Ground was a provocation to the profession to think harder about what we share intellectually and physically in terms of our inspirations, our concerns, and predicaments. (5)

It’s not clear to me how many of the contributors took up the provocation to think about collective disciplinary concerns per se. In my opinion the most interesting responses to the Biennale theme localized their focus geographically or otherwise. Continue reading »

The range of research projects being pursued in the name of architecture is perhaps more broad than any time in history. Some would equate this to a trend of uncertainty of agency in the discipline. In contrast, I find the range of intellectual possibilities to be refreshing. It is possible to explore architecture in intellectual frameworks as disparate as linguistics and semiotics vs. computation or environmental performance. In recent years, however, I can identify a few areas of research that have gained particular popularity, at least in the American academic community: parametric design, “green” building, bio mimesis, material research, and digital fabrication. I would like to compare how these current preoccupations compare to that of our Spanish counterparts.

In my preliminary research I have also developed a question relating to certain terminology used by several of the participating architects, which is the use of the word “emotion.” Perhaps I am misinterpreting, but my initial reading is that much of the Spanish architectural community strives to find a balance between “reason” and “emotion.” In contrast, I feel that the MIT architectural community is far more invested in purely questions of “reason.” I am interested in exploring these differences.

Perhaps the combination of “reason” and “emotion” is intriguing to me because I find the most exciting progress happens in architecture not from innovation within a single aspect of architecture but from a confluence of technical innovation and “non-technical” affect, whether that be programmatic, social, psychological etc. Therefore, I would like to explore how the Spanish architects are using innovation to influence our quality of life and how that compares to other architects around the world.

I believe that no individual research program, ideology, methodology etc. holds the key to innovation in architecture, but instead innovation is the result of a certain intellectual agility. Each architectural problem presents a unique opportunity for design innovation. Innovation as a definition means something new, something previously unrecognized, therefore, any attempted rigid definition would not only prove to be insufficient, but in fact be detrimental, inhibiting the spectra of possible architectural futures. Instead, I am in the process of producing a comparative analysis of various research projects within the Spanish and international architectural community.

The National Pavilions had just packed up their construction toolboxes and opened the doors to the eager crowds of archi-tourists, when the “Banal” came by. Wolf Prix’s libel against the 13th Venice Bienniale and its Common Ground aspirations, featuring punchlines such as “this event is an expensive dance macabre” or “it cannot get any worse,” flooded social networks and the architectural press spicing up the proclaimed “banality.” The accusation was the familiar lament that the Biennale is yet another venue for starchitect(o)urism, exemplifying all that goes wrong with the profession and establishing its self-indulgent distance from pressing problems of the built environment. The response was the same. David Chipperfield denounced the x-factor-like showrooms and the role of the architects as “urban decorators” setting the ground for the revival of a discussion that had been suppressed in the past decades of architectural euphoria: the architect and the many.

Perhaps preoccupied with the personal agenda of discussing fantasies of architectural democracy, this discussion was absolutely fascinating to me. Not for its ethical implications, nor for its novelty, but precisely for the lack thereof. In the 2012 Venice Biennale, the participatory project timidly rose from its ashes, to form the large counter-argument – an antistar moralism. The historical alter ego of the 1971 Design Participation Conference agenda: people instead of starchitects, empowered to express their own hypotheses, shape their own worlds, design by themselves, empowered by resilient technical infrastructures: networks, tools, systems, data. MVRDV’s Freeland, Ecosistema Urbano’s SpainLab wonder-room, Guallart’s city protocols or even the US Spontaneous Interventions, were some of the examples of a new architectural optimism engendered within a growing anti-professionalism and a call for science, interdisciplinarity and social responsibility.

Stories are made to be repeated, and so are architectural techno-social evangelisms. What is to be learned from these recursive narratives, and how do we move forward? I for one, was intrigued to find the democratizing=(?)innovating question pervading the Biennale, in the discourses of its fierce opponents and the works of its participants. Time to address it, I think.

Arch-adapting is the adaptation of architecture through environment, people and technology. With environmental data emerging through technology, we have shifted mentalities towards a sustainable goal that mirrors the simplicity of the original architectural process. A visualization of the timeline of this process depicts a frequency where architecture is evolving back to the beginning. Through Arch-adapting we are able to dissect the timeline of innovation in architecture and get a clear view on where we are and where we are going.

Subject author/ Supervisor: Nota Tsekoura

Project/Essay development: Gabriel Bello Diaz

Continue reading »

Innovacion in architecture so that architecture won’t be its own innovation victim.

If we start from the proposition that innovation is synonymous of improvement or refinement in its most basic sense, there is no better example than the evolution of architecture along the time, when it was conceived to cover the minimum needs.

This is how it shows the change of mentality legacy in current use and enjoyment of what we appreciate as past or old, simple examples are the religious buildings and fortifications that have survived to this day, have not ceased to reinvent until disappearance of, for example, the need for specific defense as a person.

Legacy present with names in the Egyptian pyramids, Acropolis Greek cities Roman fortifications and Romanesque churches, Gothic later …However this change as scheduled, answer those basic needs of life until people end up making architecture, a tool in their way of life, due to the evolved society that is generated in the industrial revolution.

Thus man becomes his own new city center and in vivo legacy enjoy today as an economic and societal. The great city expands itself to accommodate all those who went, and that invested in its best industry. The architecture would be applied to planning your victim committed. Victim of innovation.

Some, like Howard with its garden city or Arturo Soria’s lineal city had longer perspective of the technical and sophisticatedinnovation danger.

They all and knew that in a few decades it’s going to be possible to cover exponential minimum conditions of health and hygiene, and tried to propose models not overcrowding were based solely on production.

Today, many years later, we are at that point, in wich innovation has permitted use technical architecture in the collapse of large cities at the expense of idolatry to production that does not respond to the changing society.

With this innovation we are able to generate high levels of life in a context that begins to fail in all areas, no supporting emotional and / or cultural needs. Crisis at all levels.

Political crisis, financial crisis, enviromental crisis, socila crisis, global crisis.

It is therefore necessary to note that the perceived value to innovation in architectural design is limited and that the margin of tour production is not very big as engine innovation.

Innovation in architecture, as a tool, becomes into an habit that is not filled and which leads to loss identity values and belonging to the expense of production and prompting a consumer mentality that assumes it. The ability to generate new social structures unlike the citizen, and anonymous, in cores first, second or precarious category, but all well resolved.

It is proposed that the bet with the architectural innovation of the moment should be based on the technical means to develop and develop efficiency goals to implement the values of sustainability and energy awareness, but they all applied in a structure which overcomes the production and consumption model entering into a inevitable loop.

That is, beyond the innovation that allows us to develop the best techniques for know from properly apply.

The future is not innovation, but be innovative.

Continue reading »

The Academic Lab is composed by students of different national and international schools of architecture. As young innovators, they provide multiple academic lenses for innovation in architecture.

The Academic Lab members will be traveling to Venice during the opening of the Architecture Biennale to develop their projects and share their experience and will be gradually posting the process and results of their research.

These are the schools enrolled at the moment:

MIT, Massachusetts Institute of Technology / SA+P Department of Architecture

ETSAM, Polytechnic University of Madrid / Superior Technical School of Architecture

UEM, European University of Madrid / School of Architecture

IE University / School of Architecture & Design

IAAC, Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia

UFV, Francisco de Vitoria University / Polytechnic Superior School of Architecture

CEU, San Pablo University / Polytechnic Superior School of Architecture